Reflections on practicing the first of Campagnoli’s Caprices

At long last I am ready to share my initial thoughts after delving into my self-imposed boot camp of Campagnoli Caprices. The first thing we see when we open the book is a part-preface, part-manifesto by William Primrose, who edited this transcription. An apt warning for challenges ahead, its rather sassy tone still delivers a meaningful point :

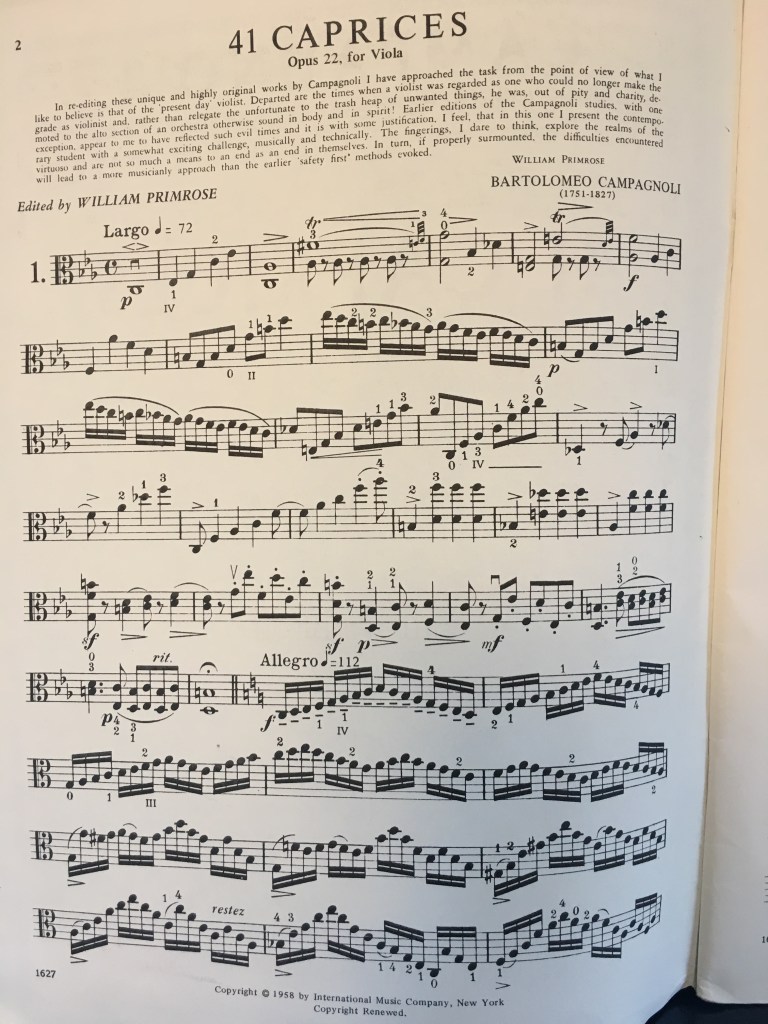

“In re-editing these unique and highly original works by Campagnoli I have approached the task from the point of view of what I like to believe is that of the ‘present day’ violist. Departed are the times when a violist was regarded as one who could no longer make the grade as a violinist and, rather than relegate the unfortunate to the trash heap of unwanted things, he was, out of pity and charity, demoted to the alto section of an orchestra otherwise sound in body and spirit! Earlier editions of the Campagnoli studies, with one exception, appear to me to have reflected such evil times and it was with some justification, I feel, that in this one I present the contemporary student with a somewhat exciting challenge, musically and technically. The fingerings, I dare to think, explore the realms of the virtuoso and are not so much a means to an end as an and in themselves. In turn, if properly surmounted, the difficulties encountered will lead to a more musicianly approach than the earlier ‘safety first’ methods evoked.”

I must admit that I adhere all too often to the “Safety First Methods” to which Mr. Primrose alludes, and that much of my recent self-criticism is related to my unwillingness to use more interesting fingerings in orchestral settings. It is part of the job to be aware of the fingerings your colleagues are using, and sometimes even if it isn’t written in the part to do so, if the others are generally using up-the-string fingerings it will make the section sound worse, not better, to opt for first position. Despite knowing this, I still fight a very strong propulsion to chicken out, play the fingering I know I will not mess up, and choose what I see as the lesser of two evils.

So, I’m going to face the problem head on. Without further adieu, let’s dive into the discomfort zone with Caprice no. 1.

Caprice no. 1 in C minor

The Largo begins in the particularly resonant key of c minor. Immediately the fingerings are, as we were warned, more creative than strictly necessary and as a whole the entire introduction could be very easy but is made pleasantly challenging simply by the fingerings. In addition to the obvious challenge of playing notes in tune, the sul c lines were especially helpful in helping me realize how much I’ve been ignoring my bow arm on the c string. In fact, with sul c and sul g passages the bow is just as crucial as the left hand in deciding whether something will sound in tune. I’ve found that my left hand might reach the note successfully but my right hand has to change, often in speed or in contact point, in order for it to sound correct. I’m more conscious now of how much arm weight is required to get the c string to vibrate at all, let alone to keep it vibrating consistently and with musical intent.

The end of the introduction also uses some constricted half-step fingerings that are quite unusual. using fingers 1,2,3 and 4 all within four half steps of each other is something of a tongue twister and has been a good workout for my brain to make sense of. I can see this type of fingering coming in handy for alternating double-stop sixths that have no other solution, so I’m happy to work this into my toolbox of fingerings.

The Allegro section, a series of seemingly simple scales and arpeggios, is also made much more challenging with up-the-string fingerings. Detaché strokes indicate even more clearly whether I’m using my bow efficiently on the lower strings; more bow changes create more chances to unintentionally change the sound, to fail to catch the string correctly and get unintended overtones. Going up a string, making it dramatically shorter, also increases the chance of this. Similarly to how there’s an optimum bow speed, bow weight and contact point for each open string, there’s another set of all of these things corresponding to each upper register of each string.

Luckily, we have 40 more caprices filled with opportunities to refine our upper-register technique.

Additional challenges of this Allegro section include string crossings in the arpeggiated section, coupled with more adventurous leaps into the upper positions. Arpeggiated passage work always gives me a sense of short-term dyslexia and it’s challenging just to get through the passage at a quick tempo without any lapses in confidence. It’s one thing to practice passage work and get it up to tempo while also internalizing the patterns, which anyone can do, and quite another to sight read it, taking in as much information as possible immediately. Reading as I play, keeping one eye on what I’m playing and one on what’s coming up, is also a skill I’ll refine very much doing passages like this.

One last thought about this first caprice is that I appreciate the fact that we began in the key of c (and eventually C). This is the friendliest key to viola players and, since our open strings all resonate in this key and our lowest one is the tonic, hearing whether something is in tune is easier than in any other key. I can tailor my intonation to the instrument; if the instrument “likes” the pitch it will resonate much more than it does when the pitch is slightly off. In keys like C there are also many opportunities for natural harmonics, which Mr. Primrose made good use of here in this introduction, and these also provide benchmarks as I travel up the string, checking if the stopped notes are in agreement with the harmonics around them.

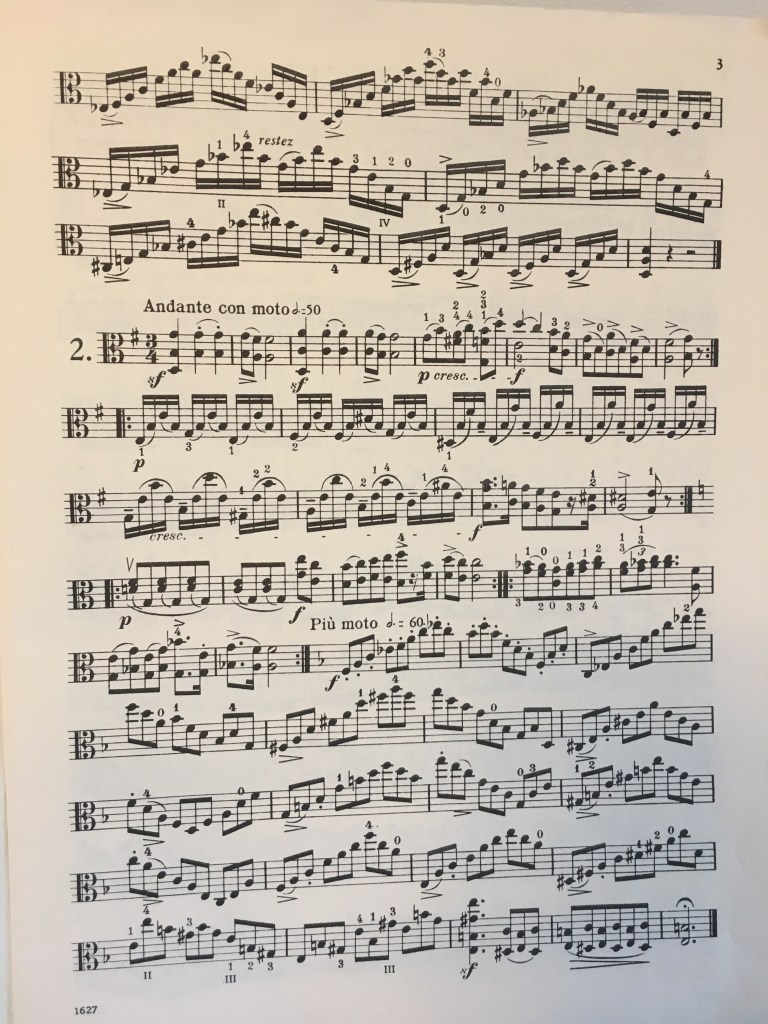

This caprice ends in a satisfying dominant cadence relative to the second caprice, so they could be played in immediate succession as one Mega Caprice. But my arm needs a rest from all those sul c and sul g’s, so we’ll save Caprice 2 for another day!